Introduction

Many people have written on this subject, but I thought I would bring a perspective from the providers of support to teachers and learners. There are three lenses that I think will be useful in considering this problem:

- What have we learned from the experiences of Covid, and the need for human interaction to support the wellbeing of learners

- How should education shift in an information rich world?

- What have we learned from the past impact of new “transformative” technologies?

Human in the loop

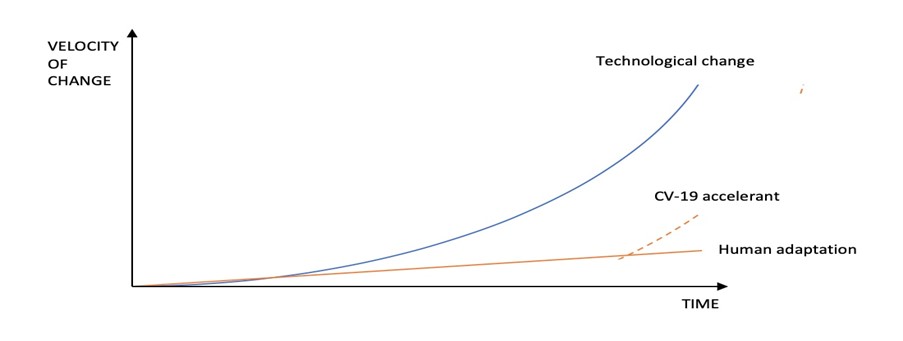

It is without doubt that generative AI has emerged as a transformative force in K12 education and beyond, offering unprecedented opportunities for personalized learning and creative exploration. However, we have also just emerged from the largest experiment in digital enabled learning in human history, and we are beginning to learn the lessons from home learning and Covid. Primarily, across the world and in developed and emerging societies there is crisis in pupil wellbeing. Attendance is down, scores in international comparative tests are stalling in many countries and support for children’s mental health is under unprecedented pressure. Alongside this, many schools are rolling back some of the technology platforms that supported learning through lockdowns in favour of face to face learning. What does this tell us? Face to face teaching has a significant impact on the wellbeing and attainment of pupils.

Therefore we need to ensure that technology, and AI in particular, are supporting the “blended” approach to delivering learning, with the teacher and classroom at the heart of learning.

Moving from a knowledge rich to a skills based curriculum

We have established that face to face delivery is a core element of the future delivery of learning. But what is the learning that is being delivered? Commentators and educators have long argued that current model of delivering learning is based on a 20th century model. There is little value in the current focus on teaching and assessing declarative knowledge, when many questions can be answered by asking Alexa, and more complex questions are being increasingly well answered by AI. Rather it is increasingly important that we focus on the skills required to function in society – much has been written on this, but core to the AI discussion are the skills of deconstructing a question into a prompt, interpreting the output of AI and synthesising a new and personal response from the output. Alongside the “traditional” 21st century skills, (collaboration, communication, creativity, critical thinking etc) we need to build a curriculum that enables learners to contribute effectively to society.

How long will this take?

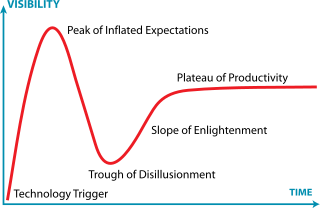

As I wrote in my previous blog post it is useful to compare the noise around generative AI to the two other technologies that were predicted to transform education in the last decade- adaptive learning and blockchain. The hype around Knewton, and the vast amount of investment raised, did not replace the teacher as many predicted. Adaptive learning platforms are now a part of many courseware solutions, but are no longer the focus of the investment community. Similarly, the crypto/ blockchain revolution was slated to change the way education and credentials were delivered. This may happen, but there is no real sign of it yet. However, I believe that AI, and Generative AI in particular will have an impact on learning. It is useful to refer to the Gartner Hype Curve:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gartner_hype_cycle

Currently we are still attaining the peak of inflated expectations. For an education technology to be successful it is not enough for it to enhance the learning experience. It needs to be embedded in the ways that learning systems work, support curricula and enhance the assessment systems that passports learners through their lives. Many technology stumble on this – they may be effective, but they cannot be blended into existing classroom approaches.

And also note there are a vast array of ways that AI will support education – replacing routine tasks, lesson planning, drafting reports and home school communications, and supporting whole school reporting. These and other uses should massively increase the efficiency of educational institutions.

In conclusion

Generative AI has the potential to revolutionize the way we approach education. By leveraging adaptive algorithms, it can create customized learning materials that cater to the unique needs and learning styles of each student. This technology can generate practice problems, interactive stories, and even simulate scientific experiments, providing students with a rich, engaging, and diverse learning experience. However the human teacher’s role is irreplaceable. Teachers bring empathy, understanding, and a personal touch that AI cannot replicate. They are skilled at interpreting students’ emotions, providing encouragement, and fostering a supportive classroom environment. And the curriculum and resources hneed to transform to prepare learners for a world where they will harness the power of AI.

Notes

I am merely scratching the surface of how AI will transform education here – I am sure I will write more on the subject. But I am indebted to many sources of information and insight in this area – including:

- My ex-colleagues at CUP&A

- Rose Luckins and her many publications (check out the Educate Newsletter The Skinny and AI in Education Podcast https://theedtechpodcast.com/edtechpodcast/

- I have found the writings of Nick Pokalitsky very useful – both in providing a background to AI and the way it builds knowledge models and how AI can be harnessed in the classroom to support the teaching and learning of creative writing. https://substack.com/@nickpotkalitsky?utm_source=substack&utm_medium=email

Also, I asked ChatGPT 4 via Windows 11 CoPilot for its thoughts on the subject. Some were useful and are reflected in the above. However, as will be the case for some time the blog post has been unrecognisably transformed by the addition of my experience, thoughts and narrative style. I hope.